1980s Films and Now

How did the way films are made change between the 1980s and today?

It’s been years since I hopped off the path of film historian and cinema theorist, but I still love the topic and frequently follow discussions as I find them online. I recently ran across this comment as part of a Tumblr thread and posted it as a topic of interest over at Round Table Writers. A great exchange with a friend followed, looking at how the film industry has changed, and poking at some of the “why's” as well as the “What does it matter’s” of the topic.

that crunchy vibe that 70s/80s movies have that modern movies simply cannot capture… that kind of quiet empty vibe to em that can be played for either bleakness or a peaceful energy… why do all modern movies (even the great and pretty ones) feel overproduced after watching an older film. what is it I can’t put my finger on it but it’s there I can feel it

A brief overview of the issue with modern films

One of the commentators on the Tumblr thread posted about how modern Hollywood films have been standardized to follow a specific “beat” pattern as a uniform template across the industry. They referenced an article in Slate by Peter Suderman that dives into this, where he calls out Blake Snyder’s 2005 book Save the Cat which was one of the more modern examples of an exploration of this type of standardization (but by no means the first).

But some of the other commentators brought up interesting points as well about the nature of the technology behind film making now vs in the 1980s.

- Shot on film

- No digital colour grading (today’s films are horribly over processed)

- No in-the-computer composite layered scenes with virtual sets etc. practical sets and effects — hand painted mattes / hand animated vfx

- You used the light you had instead of endlessly tweaking it

- Sociologically, people stopped going to movies as much in the late 1960s / early 70s because television had really taken off, the era of the ‘tv movie’ started, so studios greenlit a lot of low budget auteur films that had to focus on meaning & relationships instead of spectacle.

And another brought up average shot length

it’s not just pacing but also average shot length (sometimes shortened to “ASL,” but not to be confused with american sign language.) a movie that only cuts every 12 seconds is gonna feel drastically different from a movie that cuts every 2.5 seconds.

My friend made some great points regarding this discussion, especially the concept that standardization of script format is a symptom of something larger, not the thing in and of itself.

So many thoughts! 1) The most important thing in the story is missing. What examples of movies is the OP thinking? Because I remember the 70s-80s as the era of Meatballs and Porky’s and Police Academy and Revenge of the Nerds and (if you’re feeling posh) Animal House and Caddyshack and Fast Times at Ridgemont High. The grimy VCR cassettes at Blockbuster. And I don’t think of “TV movies,” I think of “direct-to-TV movies.” “Quieter,” “more thoughtful,” “uncapturable,” “lost greatness” — these are not ways I’d describe 80s film. There might be more uniformity among movies today, but that’s because movies are pursuing a declining audience that will reliably come out for spectacle but not for much else. So what you get is the opera of our times. A more interesting question for me is why “direct-to-TV movie” hasn’t lost its pejorative connotations even as TV has become more respected than film (I’d argue). Why don’t we like short form in TV enough to be excited by TV shorter than a miniseries? Or have people started tuning in to that sort of thing and I’m still behind the curve…

Is it just because movies look tired if they get to sequel 5 and TV comes with a dozen built-in sequels per year, so the economics are more pleasing to entertainment companies?

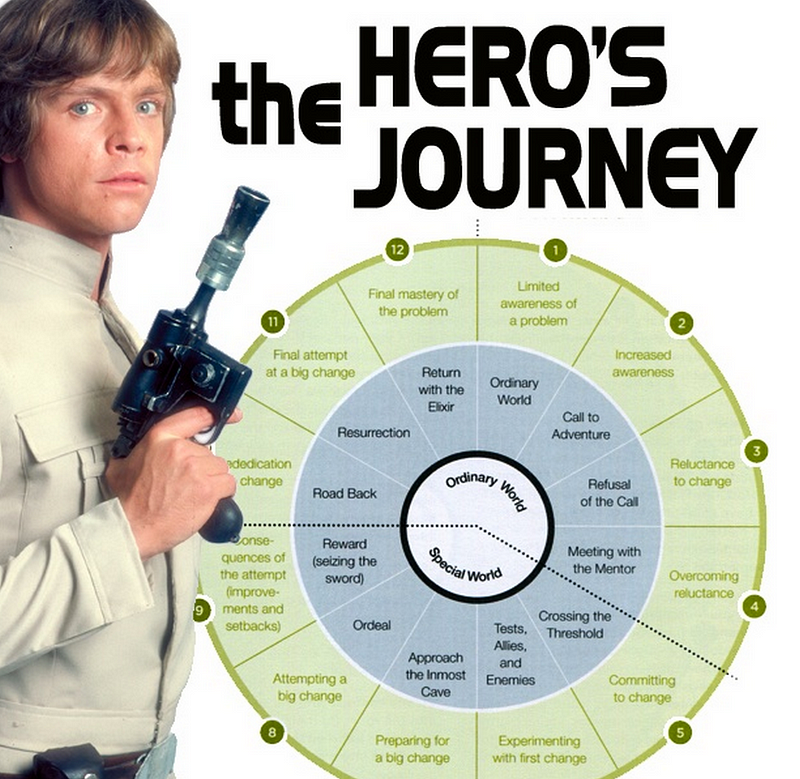

Also, people blame it on Snyder, but McKee and Field were teaching it before him. And neither of them is the true progenitor. It’s like the Hero’s Journey. They’re dramatic formulas, the power cords and major key of storytelling. A writer can try going without them, but if they fail, I wouldn’t blame it on the audience.

The Hero’s Journey

Ah, that’s something I find fascinating because the Hero’s Journey isn’t necessarily a template to follow, but rather a description, an observation, right? So, we do end up taking the observation of the things that seem to work, or the things that seem to occur with frequency and elicit specific responses, and then we codify them. Sometimes, that leads to new things that work consistently, but I think the point that’s more interesting is “what do we lose?”

TV movies generally seem to be a pejorative stand-in for specific examples of a certain type of low-budget films designed to be easily consumed at a time before modern dramatic series existed. But there are examples I know I could find of TV films from that era (and mostly any era) that are actually really good.

But there’s also so much else going on in film history in that era because while there were all those rather ridiculous big-budget films (many of which were just adult slapstick, many of which were comedies), we also got another range of films as we exited the 70s that were more auteur and yet somehow made big waves with various segments of the movie going population: Blue Velvet, Ran, Aliens, Blade Runner, After Hours, Amadeus, Breakfast Club, heck, even Out of Africa, that were not necessarily all blockbusters, but which all did so much more. I’d say there was a blending of the ability to be popular and the ability to do really fine work. But, what the Tumblr commentator was talking about…

Is actually what interested me the most originally, and the direct responses to them.

I’d seen the “beats” article before and thought pretty much the same as you: it’s part of the puzzle, not the solution. Attempting to adhere to a specific rulebook that prescribes how a writer must write has never seemed like a good idea to me, and Hollywood is absolutely guilty of doing that at almost every level.

There might be more uniformity among movies today, but that’s because movies are pursuing a declining audience that will reliably come out for spectacle but not for much else. So what you get is the opera of our times.

I really love the point here and the phrase “opera of the times” and think it’s incredibly apt — that’s exactly what the Marvel films, for instance, are. There can be random breakthroughs (WandaVision managed to do meta-commentary at the same time as solid emotional storytelling, even if the “last act” of the season fizzled a bit), but it’s largely all working off of one mold, and it’s not even a mold that’s particularly faithful to the point and passion of the original comics (which were frequently subversive and powerful, just as they were frequently ridiculous and… bad, lol.

Again, people are going to the movies less these days, just like when TV first started, but I’m curious about whether or not there’s a similar rise of really solid filmmaking that’s able to buck the trend — and I’m curious about the reasons for the OPs musing about the changing quality — the ineffable “something” that the films of the 1980s had.