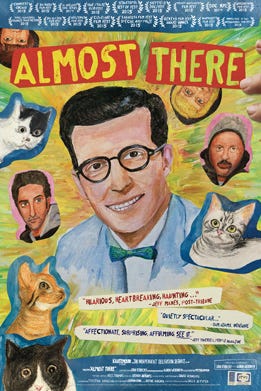

Almost There brought up some interesting themes through its narrative that were complimented nicely by its relaxed artistic style, which mirrored the work of Peter Anton, the artist at the center of the documentary. Created by Dan Rybicky and Aaron Wickenden, Almost There is a thought-provoking film, just entertaining enough to mostly draw the attention away from the relatively simple “run-n-gun” style production. It is a good viewing choice for anyone who questions what an artist means to the society — as well as anyone who has questioned whether or not a work of art can be separated from the artist.

Introduced to Peter Anton, we are alerted to his fragile mental and physical state without hardly any prodding by the narrator. The burgeoning sores around the edges of Anton’s mouth, the unkempt state of his wispy hair; Anton has the wild-eyed demeanor of a man who has lost connection with his surroundings. It is hard not to feel bad for the small old man as he sits under the shade of a temporary outdoor canopy, relatively ignored by the majority of the passerby attending (of all things) a pierogi festival. At one point his exclaimed “come over here, let me paint you. I’ll paint you for free, let me paint you!” inspires a mixture of empathy and mild unease. Here is a reminder of the end-years of a human life, a subject many would rather not contemplate at all.

Anton’s on-the-spot portraits are crude drawings in bright pastels — flat and uninviting. Several shots of Anton’s work slide by on the screen, but the last, one with startlingly alive eyes, holds the attention. The goopy pastels that make up most of the work feel like a child’s innocent attempt at art, but the eyes of the final drawing hold something deeper, a subtle merit which cannot be ignored.

A year passes after the pierogi festival before the filmmakers return to Anton’s life. Invited to his home in East Chicago (a small town not actually part of the city Chicago), they introduce the audience to the squalor and decrepit reality Anton (and many like him) call home. Burned-out and condemned houses, cracked streets, and a friendless glaring sun all cement the portrait of a dark reality to American society. Anton’s house especially so, as the filmmakers realize that the basement of the building where Anton lives is too moldy and filled with noxious smells for them to enter without masks. They must return the next day.

As the film moves on, the viewer is introduced further to Anton’s subterranean existence, hunkered away in a bunker of mummified cat remains. Something else also becomes visible in the gloom, as the lens and light attached to the camera creeps through the shadows of a decayed life: the reality of Anton’s art. Beyond the crude portraits at the festival where the filmmakers first encountered him, Anton’s collection holds a wealth of material that shows a unique perseverance. While never “grand,” his work depicts a certain tenacity and poignant humanity which refuses to be undone by the horrid surroundings. In a series of colorful binders, Anton’s entire life story is laid out before the viewer in old photos and hand-drawn additions. It is timeless work in its own right showcasing the reality of a life’s day-to-day workings through the course of years. It is impossible to look upon this collection and not feel a sense of heartbreak at the entropy Anton seems in such close personal contact with.

As the documentary continues, the narrative occasionally cuts to snapshots of Dan Rybicky and his relationship with his brother and mother, drawing startlingly clear relationships between their lives and Anton’s that leave a humbling and almost chilling feeling in the mind. This personal connection to one of the filmmakers further draws us in and sets us up for the unnerving shift in the narrative to come.

The filmmakers befriended Anton over a period of a year, all while filming his life, and Anton had become unhealthily reliant upon their company. They film shopping trips they took him on, and minor repairs to some aspects of the house (quite ineffectually) they had attempted to provide. The culmination of this relationship was an art exhibit for Anton’s autobiographical collection, and his life, at Intuit, a center for “outsider” artists whose lives could easily be considered outside the “norm”. At first, this seems like it might be the fulfilling end of the film — the happy moment upon which the screen fades and the credits roll. But Anton has a dark history that the notoriety of the exhibit unknowingly disturbs.

I won’t say what Anton did because doing so might ruin your viewing of this documentary but it suffices to say that he has punished himself in a way no external authority ever could. Many of the participants in the talent shows he hosted for 17 years before the scandal are interviewed and describe a charismatic and kind showman far removed from the broken hermit we see in the film. All he’s got left by the time we’re introduced to him are memories and stacks of materials from the past that threaten to literally bury him alive. The wrecked house is all that he has, yet leaving it turns out to be his only way to salvation. ~ “Almost There” Gets There by Dmitry Samarov

The uncovered revelation serves to remind the audience that this is not a Hollywood screenplay, where everything is settled into neat and identifiable patterns. The audience (along with the filmmakers themselves) are suddenly forced to ask the question “can the art be separated from the artist?” Since several other artist exhibits at Intuit feature the work of people with similarly uncomfortable backgrounds (but who are long since deceased), the question “can art be separated after an artist is dead” is likewise posed. At what point is it acceptable to give credit to creation without unwillingly supporting the position of a morally-unsettling creator?

Regardless of the severity of Anton’s crime, or his intentions behind it, the discussion is an important one that is all-too-often glossed over in an age where daily celebrity gossip sweeps common discussion of serious subjects aside. In his article “Almost There” Gets There, Dmitry Samarov writes about his interest in a documentary that provides a realistic view of artists — the “shades of grey” versus a “black and white” portrayal of their lives. Certainly then, in this case, the filmmakers have hit that mark, making Samarov’s title apt. Almost There does not sidle by the muddier waters of Anton’s life, but rather uses it to catalyze a much larger discussion.

This sort of documentary is not a double-blind project. Here the filmmakers are directly involved in the subject of their work on a deeply personal level as well as the professional. Their actions become as much a part of the narrative as those of their subject, and what they choose to do (or not do) can dramatically impact the very real life of the people with whom they become entangled.

In this case, Anton’s entire world is changed because of their involvement, as are the lives of many others who become caught up in the story. Anton’s artwork is displayed to the world — as is his disreputable past, and the questions raised through this process provoke widespread discussion far beyond the crumbling confines of East Chicago.

A documentary like this is more than a static lens on the interactions of a distant world, it is the unyielding coexistence of artist and subject on the field of daily life and daily emotion. By getting right down into the muck and grime of existence — by allowing their lives to blend deeply with that of their subject — the filmmakers provided a powerful message: that art is not static, something to be looked at and then ignored — art hits us human beings where it matters. It casts light on the connections between ordinary people that so often go overlooked during the frantic rush of daily existence, and forces the viewer to pay attention to things they might otherwise overlook.