Critiques, genius, and how art can change the world.

When I was nine years old, my parents gave me a couple of books to read: Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn. I’d never exactly been a sheltered child, but experiencing these frank accounts of the worst aspects of the country I lived in shook me, and I remember crying as I read about the horrors people had undergone in the name of various “frontiers.”

Of course, I also knew that American Indian peoples weren’t a relic from the past: my parent’s connections to native friends assured me of that bit of knowledge. Not all of my peers were so lucky, however. As a White boy within a mostly-White community, my knowledge lived in an outsider bubble that rarely got unpacked. Even among home-schooled progressive families, these issues were often taught as history rather than an ongoing experience.

I preface my review of Killers with this because my primary critique of the film relates to this frequent aspect of a White perspective. Namely, that native stories are historical tales of horror and pain. This is a problem because native communities exist all over the country — and these historical stories are part of an evolving tapestry of history. The context of the past must be understood within the context of the present: real people, with real lives, feelings, pains, and joys.

To his credit, I think Scorsese pulled the film farther toward this nuanced perspective than the studios had originally intended. The final scene of the film (no spoilers, yet) offers us a glimpse of the modern context in a really powerful way: these are people who are still here, who still thrive. But Killers could have done more to pull the narrative into the 21st-century… if only because the final battles related to the events of the film weren’t done playing out until 2011.

When the Osage people were forcibly relocated by the United States government to the Reservation in Oklahoma, they were able to retain mineral rights to their new home. These rights proved exceptionally valuable when, in 1897, oil was discovered on their land. Steps were soon taken by the Federal government to administer these funds, forcing a guardianship system upon the Osage — the same system depicted in the film — and it led to widespread mismanagement and fraud by outsiders (especially local legal “experts”) trying to get rich of Osage wealth. I’m not sure how many of my readers will be able to recognize the sheer degradation of such an experience, but Lily Gladstone portrays the rage and humiliation powerfully on the screen.

Killers of the Flower Moon deals with the mass murder of Osage by greedy outsiders, and touches on some of the mismanagement of their funds as a whole, but what it doesn’t do is explain that the Osage didn’t find some measure of legal recompense until the year 2011. Their lawsuit against the United States began in 2000 and continued for eleven years, finally resulting in a victory that presented them with monetary damages against the State. As I pointed out earlier in this article: these are people who are very much still here.

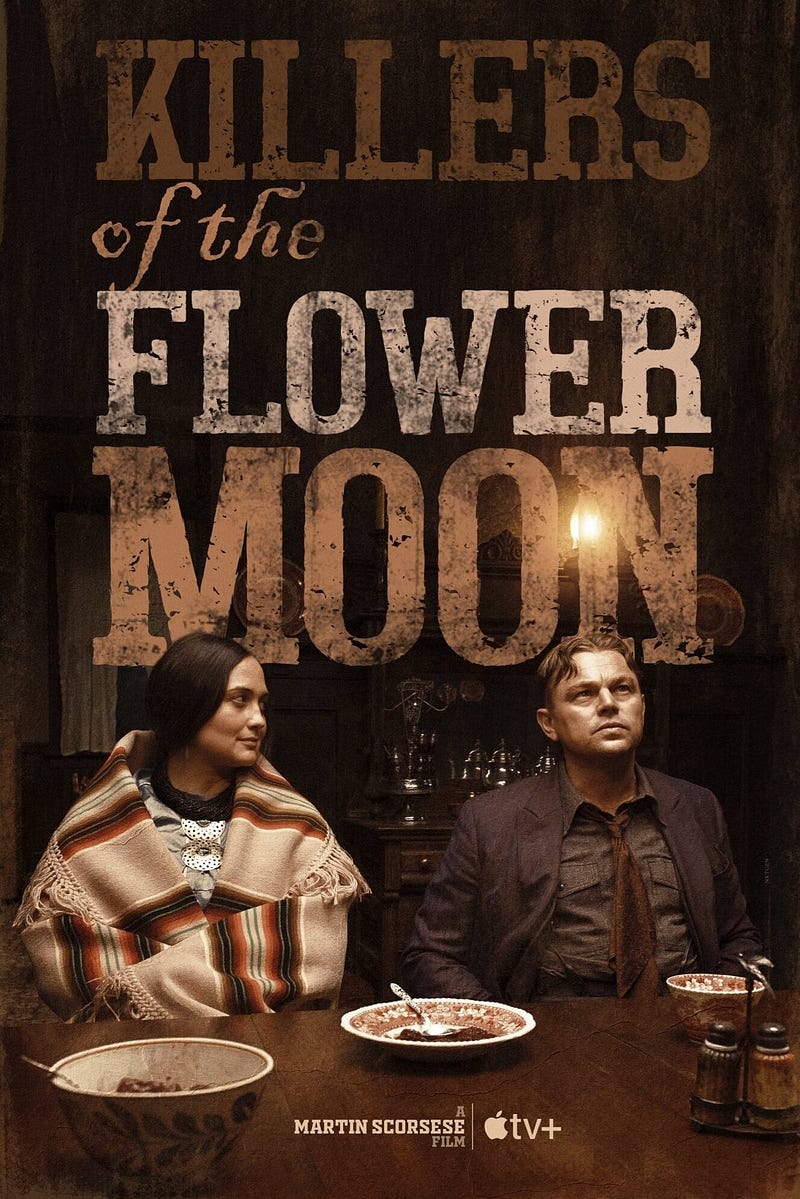

There is no doubt in my mind that the film, as a whole, is superb. Made with Scorsese’s usual deliberate care for quality, strongly supported by the Osage nation during its production, and replete with a cast of uncommon skill, Killers of the Flower Moon is a masterpiece. At almost three and a half hours, it calls us back to a deep cinematic experience of immersion: something that’s fallen by the wayside in our hyper-busy, over-connected world. What’s so amazing about Killers in this regard is that it doesn’t feel especially long. The pacing is, in all save a few points, perfect, and the tale itself is delivered in such a way that you can’t bring yourself to look away.

It’s also not a film for the faint of heart. The world is dark, and full of terrors, and the society we inhabit is one that has condoned (and still continues to condone) brutal behavior upon human beings both here and abroad. The depredations foisted upon the Osage are not an isolated example of the United States abuses of power, nor are those abuses confined to some historical study. From coups in socialist countries, to continued genocidal behaviors against Indigenous peoples here at home, to continued segregationist practices, to renewed violence against LGBTQ+ people, to the ongoing war against people of all backgrounds whose greatest sin is being poor: our country has not changed all that much from the one that murdered millions (and enslaved millions more) in the name of profit. Those twisted roots are deep.

But stories like this have power to shine light on past injustices, and help those who suffered through them experience the light of public recognition. Art allows sorrow to be shared, and for anger to be honed and directed toward action for the greater good. Little bit by little bit we can claw our way into the hearts and minds of the uncomprehending and the willfully obtuse, and from there maybe we can start to foment some real change.

So, go see Killers of the Flower Moon and bring your friends. Bring your shitty racist uncle and your apathetic 20-something friends. Even if they don’t understand what they’re seeing in its entirety, art has a funny way of slipping through the cracks in our mental walls, and it might just start fomenting some changes in the world. For those who have links to this story, or any of the thousands of stories like it, go in with planned self-care, and community support you can rely on, because art also has a way of opening old wounds (some of which we’ve been carrying for generations). But, no matter the reason: do go see this film. It’s worth your time.

Your support means the world to me

Hi there! I’m Odin Halvorson, a librarian, independent scholar, film fanatic, fiction author, and tech enthusiast. If you like my work and want to support me, please consider subscribing!