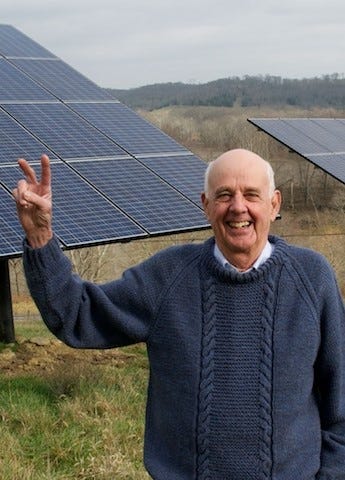

One World, One People: Ruminating on Wendell Berry

Wendell Berry (born 1934) is an intellectual writer, philosopher, conservationist, activist, Christian, and small-farm advocate. A devout…

Wendell Berry (born 1934) is an intellectual writer, philosopher, conservationist, activist, Christian, and small-farm advocate. A devout Christian and a native Kentuckian, Wendell’s work is broad and intimate at the same time, never settling for the simplistic answer when the situation calls for deeper reflection. Berry’s work bridges time’s seemingly impermeable river, allowing us to ford the waters between those simpler days when technology had not yet overtaken the world. And, yet, Berry is not a crusader against the evolution of the old into the new, but rather a careful contemplator and watcher, a man who sees the new as beautiful… yet deadly, too, if handled carelessly.

The collection of essays I am discussing in this series, Our Only World: Ten Essays, is concentrated on the ecological state of the world today, amid the rise and sprawl of industrial technology.

Throughout these essays, Berry deftly considers the practical importance of a stable and secure environment alongside the relatable need of families across the United States to support themselves. By looking at the world through a complicated, less reactionary lens, he removes some of the ideological pretentiousness which creeps in on both sides of such arguments: for Berry, a sound ecological state is one where the land can be used, worked, and lived off of without destroying it; the world is our only resource, he seems to say, so it only makes sense to conserve it, tend it, and use it well.

In far too many of the debates happening in America right now, the polarization is so extreme that people cannot talk to one another about the issues that matter. Fear has taken hold and has led to anger from all sides, bending this great nation back upon itself as a snake upon its tail. Without open, willing, neighborly communication, little can be done to produce the sort of quick social growth required to stem the dangerous deterioration of the world around us. The tide of catastrophic climate change is sped on, ever faster, by the greedy elite, while the ordinary people are left fighting one another. That is not the way things should be. There is too much name-calling and not enough brotherly consideration.

Berry, who himself hails from a landscape where many of the voters have been, in recent times, more “conservative” (if such titles mean much of anything) his words hold even greater importance. In these essays one is reminded of the earnest people who live on the land and derive their livelihood from that land; an understanding of “conservative” emerges from Berry’s work which differs from that of the normal disparaging zeitgeist — an understanding that “conservative” means to protect and to cherish the roots from which we came. If we consider this definition, perhaps it becomes easier to understand why so much anger has emerged from the midsection of America — the old ways of caring for; of living through a deep and abiding love for and knowledge of the land, are being dismantled and reduced to Late Show parodies before the very eyes of the people who are affected the most by these changes to the land.

Though Berry clearly carries with him strong elements of his Christian upbringing and faith, he maintains composure even when discussing things he personally disagrees with. He shows the rare ability to be able to clearly state his position, and even argue it, without aggressive overtures, snide tonality, or any sense other than that he, despite his great personal convictions, believes wholeheartedly that other people have the right to believe differently than he does, and that their beliefs can exist as valid alongside his own, peacefully, despite contradictions that arise. This bridge between his Christian religious framework and the progressive ideal is one of undeniable importance in the world today. Bridges like this can allow people to work together and make changes for the betterment of all our people — without needing to agree with one another in all things at all times. This hints at an honorable path not seen in many decades among our political leaders: the ability to work together for the common good without trying to undermine one another for petty or vindictive reasons.

In the first essay, paragraphs from a notebook, Barry is focusing primarily on the concept of wholeness in the world. By this, he is meaning the opposite of the standard (or presumably standard in the modernized western world) idea of elements which are inherently separate from one another. That is: that a tree is not separate from the ground or the stream that it is near, that a person is not separate from another person, that the brain and the mind are not separate from the body, that in fact all things are connected and interconnected and interconnected again, in a vast and nearly incomprehensible net.

Berry opens with the following:

“We need to acknowledge the formlessness inherent in the analytic science that divides creatures into organs, cells, and ever-smaller parts or particles according to its technological capabilities.

I recognize the possibility and existence of this knowledge, even its usefulness, but I also recognize the narrowness of its usefulness and the damage it does. I can see that in a sense it is true, but also that its truth is small and far from complete.”

It is unthinkingly accepted by many that human beings are separate from one another. The concept of the perfect individual, devoid of all responsibilities excepting those “voluntarily agreed upon,” is a pervasive one. But, within nature, absolute individuality is a lie. It is true that there exists a realm of individual responsibility necessary for the functioning of human life and society, but that level of individuality only works when it is coexisting harmoniously with the background subtleties of the ecosystem the individual lives within. As Berry is pointing out, here, there is a fragmentary perspective at work throughout all industrialized cultures, one which separates things from each other — as if the connections inherent in the system could be so easily severed; as if the complicated interrelationships of this complex system of life that we call nature was not inexorably built through a process of millennia-long evolution.

Human beings, especially in our Western culture, delight in our individuality, with no or little thought for the holistic nature of nature. Yet, the experiences between family, friends, strangers on the street, the television shows watched, the books read — these are all relatable and obvious examples of our interconnectivity. The Barista who serves us coffee every week is a part of our life and has an effect on us greater than what might be easily perceptible. We are not individuals isolated from our surroundings, but rather products of a collective set of experiences and inter-relationships. Even further are issues of epigenetics — gene expressions altered through some environmental factor into an “on” or an “off” — and the possibility that epigenetic memories of stress might get passed on generationally (for further reading, there is this study regarding holocaust survivors, examining how intergenerational stress effects are passed down through the generations: [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.005]).

Wendell goes on to explore how our society observes the individual as an isolated entity in certain respects and as a holistic being in other respects, often in quite contradictory ways. He also questions the concept of belief and whether or not certain truths are a matter of belief more than they are a matter of simple awareness or knowledge.

In one of the most interesting sections, Wendell engages with linguistic play to poetically suggest an alternative to the models of thought which rely on mechanical separation.

“A proper attention to our language, moreover, informs us that the Greek root of anatomy means dissection, and that of analysis means to undo. The two words have essentially the same meaning. Neither suggests a respect for formal Integrity. I suppose that the nearest antonym to both is a word we borrow directly from the Greek: poiesis, making or creation, which suggests that the work of the poet, decomposer or maker, is the necessary opposite to that of the analyst and the anatomist. Some scientists, I think, are in this sense poets.

But we appear to be deficient in learning or teaching a competent concern for the way that parts are joined. We certainly are not learning or teaching adequately the arts of forming parts into wholes, or the arts of preserving the formal Integrity of the things we receive as wholes already formed.”

And this appears to be accurate: that in most cases formal education teaches us that we are individual atoms and that while we do partake of larger systems, we are intrinsically separate from any other piece of such a system. That we exist within a series of mutually agreeable contracts with other individual units, contracts which we could annul freely at any point in time. We are not responsible for our impact on other people because other people could, in this view, disassociate from us freely.

Wendell goes on to say the following:

“We have formed our present life, including our economic and intellectual life upon specialization, professionalism, and competition. Certified smart people expected to solve all problems by analysis, dividing wholes into ever smaller parts. […] In such a state of things we don’t see or, apparently, suspect the complexity of connections among ecology, agriculture, food, health, and medicine […]. Nor can we see how this complexity is necessarily contained within, and at the mercy of, human culture, which in turn is necessarily contained within the not very expandable limits of human knowledge and human intelligence.

[…]

The capitalization of fear, weakness, ignorance, bloodthirst, and disease is certainly financial, but it is not, properly speaking, economic.”

So here, Wendell forms perhaps the most interesting takeaway from an already engaging essay: that the systems which separate the world along mechanical lines are inherently contradictory and illogical. What is truly economical is that which creates the greatest amount of good — in that it supports the individual pieces of the system as well as the system itself, and that it resists the temptation to damage related systems (and their individual parts) because in the grander scheme (the one our world operates by) these related systems are interdependent systems.

Of course, we do end up with the problem of immediacy: if someone is in need of survival necessities (food, shelter, or the means by which to access these), they are going to (usually) be unable to connect their circumstances to the larger system at work. If a farmer’s land is in dire need of crop rotation due to mineral depletion and erosion, but the farmer’s family won’t have enough money to survive if they plant any other crop, they will take the short-term gain rather than the long-term view. The individual unit will attempt to save itself from destruction — that is part of the nature of life. In some readings of the above illustration, the farmer might be seen as “at fault.” They should have been more careful not to overreach their resources, they should have been more careful to diversify their crops, to begin with, they should have… should have, should have, should have… Yet, the problem is not that the individual wishes to survive but that they exist within a system which sees them as disposable unless they meet an arbitrary quota of “worth.” Individual responsibility has been turned, somewhere in recent memory, into a cudgel used to beat the common person over the head. It is the culture that causes the problems, not the individuals existing within the culture.

Only in such a state of devised-reality does it make sense to operate any industry which causes environmental degradation for a comparatively minor profit margin. The separations are false.

So, how can we make our way out of this problematical situation?

Wendell suggests that:

“criticism of scientific industrial progress need to not be balked by the question of how we would like to do without anesthetics or immunizations or antibiotics. Of course there have been benefits. Of course there has been advantages-at least to the advantaged. But a valid criticism does not deal in categorical approvals and condemnations. Valid criticism attempts a just description of our condition. It weighs advantages against disadvantages, gains against losses, using standards more general and reliable than corporate profit or economic growth. If criticism involves computation, then it aims at a full accounting and an honest and net result, whether a net gain or a net loss. If we are to hope to live sensibly, correcting mistakes that need correcting, we need a valid general criticism.”

Yet, does it go further? Being taught general criticism is important, yet one of the things Wendell constantly speaks to is his personal connection to the land. Throughout all of his essays, he stresses this point — that too often the people trying to “save” the wilderness have never spent more than a passing amount of time there; that they often completely ignore agricultural land and its uses, instead opting to support only those areas which are considered “pristine.” So, perhaps the idea of general criticism needs, also, a sense of home. A sense that the land deserves to be cared for by those it cares for — a dramatic shift from the standard model of private dominion and value-based judgments.

“Can we imagine a way of education that would just turn passive consumers into active and informed critics, capable of using their own minds in their own defense? It will not be the purely technical education-for-employment now advocated by the most influential “educators” and “leaders.”

We have good technical or specialized criticism: A given thing is either a good specimen of its kind or it is not. A valid general criticism would measure work against its context. The health of the context-the body, the community, the ecosystem-would reveal the health of the work.”

From what deep well would this sort of general criticism arise in a modern context? So many people are divorced from the land and blocked to the need for protection of the natural world. The industries responsible for the destruction of the natural world appear quite pleased with this and their various employees work diligently to ensure that the meager protections erected are emaciated or ignored whenever possible.

Yet, it is a matter of the common good that the world be preserved and aided in its natural desire to flourish. Humanity relies upon the Earth, and now, it relies upon us, to stand as faithful stewards for the future of all species — including ours.

If the health of the world right now is anything to go by, the way we’re running our societies is not working. Our context is clear on this point: we have some big problems to overcome before we can begin to look at ourselves and feel secure in the knowledge that we are doing good by our ecosystem (and, therefore, good by all the future generations who will be looking back on us and judging our mistakes and attempts to rally for the greater good).

If there is a solution to these problems, it seems likely that Berry has put his finger squarely on it. If the current generations, and future generations, can be adequately educated about the nature of the ecosystem humanity is a part of, maybe our species stands a chance. Such an education would look considerably different from the sort common today, however. Rather than a system of education designed to produce an agile and submissive workforce, we would need a system concentrating all its resources on the empowering of strong local communities and the growth of critical and self-aware individual members of the society.

At the moment one thing is clear: we cannot rely on anyone else to save us. No leader or “elite” will be enough to make the changes required in the time we have left. Instead, ordinary people must begin to prioritize coordinated efforts and direct communication with their neighbors. If the local communities can stand strong against the influence of international industry then perhaps humanity will survive long enough to honor its unintentional role as shepherd for this pale blue dot.