Richard Wright: The Best American Haiku

With Haiku, a self-nurturing could begin, albeit so close to his own death. Wright offers his perspective, his own loneliness, and his own desire for wholeness within three simple lines of poetry, allowing us to know him intimately at his most vulnerable and his most human.

I did not discover Richard Wright they way I imagine most people do, through his novels. Undoubtedly, his prose is powerful, whatever else can be said of it, but I am glad to have first entered into his mind, instead, through his haiku.

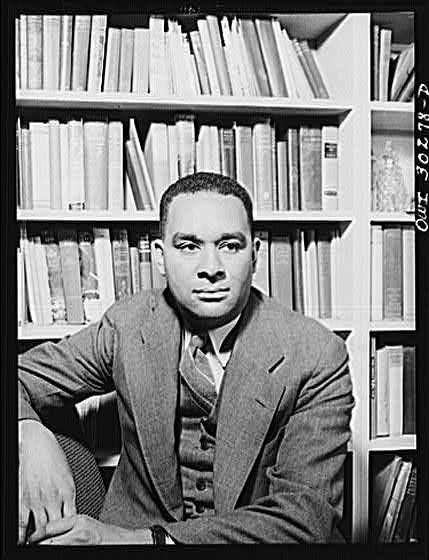

Wright, the author of Native Son and Black Boy discovered haiku during the last two years of his life while living in France. During those two years, he wrote over four thousand haiku on hundreds of subjects, capturing thousands of moments with his unique eye. In the collection I first encountered him through, Haiku The Last Poems of an American Icon, there are just over eight-hundred out of those thousands, hand picked by Wright before his death in 1960.

His daughter wrote, in the introduction to this collection, that “With Haiku, a self-nurturing could begin, albeit so close to his own death.” Throughout his life, Wright had dealt with the trauma of being black in a country that despised blackness, and, later, with the hardship of holding values which were attacked viciously during the anti-socialist fear-mongering of the Cold War by the government of that same country. As a young writer, he delved into the experience of blackness like few others before him, bringing questions to the literary world which had gone unasked and unnoticed despite the tumultuous experiences of that era.

Later in life, he would redirect his attentions elsewhere, coming to understand that the root of so much suffering in the world was the manner in which wealth plays out across social lines. In the early 1930’s Wright joined the Communist Party, struck both by the values the Party espoused and interested in exploring the literary world attached to and surrounding Communist ideals. He wrote a number of poems, including We of the Red Leaves of Red Books in direct support of Communism. Soon, however, racism brought him into conflict with white members of the Communist Party, who consistently treated him poorly and, eventually, violently. Black members, too, publicly decried him as a “bourgeois intellectual,” an untrue accusation (since Wright was, primarily, self-taught,) as well as a pointless one.

Wright would continue to hold dear his affiliation to the Communist Party until 1942 when he began to sever ties with the organization. By 1944 he had publicly withdrawn himself from the organization, citing racial conflicts as well as a deep disease and disapproval of the Great Purge enacted in the Soviet Union by Josef Stalin. He did not, however, leave his left-leaning idealism behind, but continued to believe firmly that the solutions to the problems faced in the world were those couched in progressive democracy.

He moved to Paris in 1946 and became a permanent expatriate of the United States. He viewed the United State’s militaristic foreign policy as antithetical to his progressive values and found himself at odds with the great depth of institutionalized racism inherent in the country. His career as a writer, too, had by that point suffered due to his outspoken nature and various affiliations. In France, he believed, he might still find support as many of the great writers in the past had done. In France, he became friends with the great existentialists Jean-Pual Sartre and Albert Camus and he eventually produced his own existentialist novel, The Outsider (1953).

By this point, Wright was under surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The F.B.I. were, during this time, aggressively working against progressive and reactionary groups, using everything from blackmail to outright murder to achieve their aims (later, this aggressive policy would become solidified in the COINTELPRO projects). While Wright traveled through Europe and Asia, giving talks and connecting with various literary and activist communities, he was also contacted by representatives of the Central Intelligence Agency, through the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an organization with ties to the CIA. As an American who wished to remain outside the United States, Wright soon found himself in a difficult position. In the early and mid-1950’s, Wright reported to the US State Department on activities of certain individuals of interest to the United States for the political activities and beliefs likely to ensure that his visa could be renewed. The pressure on Wright was incredible, and as his daughter wrote in her introduction to Haiku, “My father’s open querying of American counterintelligence tactics regarding radical black expatriates, his research into racial tensions surrounding U.S. army bases … (as part of research for one of his books) … his attempt to protect his friend and confidant Ollie Harrington … all these interests and loyalties culminated in the realization that he himself was being increasingly monitored….”

Because of all of this, Wright was under a great deal of pressure to avoid writing about the growing surge of civil rights activism taking place back in the United States during those years — with at least one of his articles going unpublished by EBONY and refused by Atlantic Monthly for fear of its potentially “disloyal” elements.

However, Wright would continue to strive for political resistance to all imperial powers and, towards the end of his life, began to speak out about the racial situation in the United States, as well — most notably in a series of radio broadcasts done in France.

Wright died of a heart attack in 1960 at the age of 52.

What fascinates me so much about his haiku is how elegantly it manages to capture Wright’s perceptions of the world; there can be the gentle beauty stereotypical of haiku, to be sure, but within his collection area a number of pieces which could only have been produced by someone with his experiences and worldview; haiku which are a beautiful meld between traditional qualities of 5–7–5 syllabic form with the perceptual qualities unique to Wright’s temperament and experiences.

Scholar Jim Wilson, a former Buddhist monk, former prison chaplain, and an accomplished poet, writes on his blog Shaping Words about the quality of Wright’s language in these haiku:

“First, the vocabulary is accessible by ordinary readers. There are no high abstractions or obscure words, no made-up words. The concordance appears to be dominated by nouns that name objects in the world that anyone can relate to. […] Wright’s haiku accept(s) the English language as it is. From my perspective that is one of the chief virtues of his haiku and it is an ideal that I would like to see many more ELH (English Language Haiku) poets adopt.”

To this, I agree. Wright’s language is rarely adorned with unnecessarily enigmatic phrases; his style is direct and poignant; and yet, while he writes with a vocabulary that is knowable by all, he manages to bring his haiku together in such a way that reader is afforded a true sense-experience of the moment Wright was attempting to capture. Take this example:

In the setting sun,

Red leaves upon yellow sand

And a silent sea.

Or this:

The barking of dogs

Is deepening the yellow

Of the sunflowers.

But Wright also displays a powerful ability to break from convention with respect to authorial injection into the haiku; he manages to at once capture the essence of a moment while introducing a deeper, philosophical element. Here is one of my favorite examples:

In the falling snow

A laughing boy holds out his palms

Until they are white.

The imagery is poignant not, simply, because it affords the reader a brief look at a winter wonderland, but because of the un-implied, silently playful quality of the poem, which is perhaps only intelligible to someone who has an understanding of who Wright is and where he has come from. Who, knowing of Wright’s life story, could fail to detect the symbolism inherent in such a piece?

Within his haiku, Wright displays tenderness, humor, as well as — at times — a sense of how his mind locks upon the less-savory elements of life and nature; all captured effortlessly and simply, never pretending to be more than they are while frequently containing delightful depths. I enjoy, too, the knowledge that a man who disliked rural life would eventually become so awestruck in his final years by the bounty of nature existing everywhere around him in the French countryside. Indeed, Wright frequently offers his own perspective, his own loneliness, and his own desire for wholeness within the three simple lines of his haiku, allowing us to know him intimately at his most vulnerable and his most human. I shall close with three which illustrate this most beautiful aspect of his poetry

A descending fog

Is making an autumn day

Taste of buried years.

Lonelier than dew

On shriveled magnolias

Burnt black by the sun.

A sleepless spring night:

Yearning for what I never had,

And for what never was.