The Relationship of Geography and the Inhabitants of a Secondary World

The geography of any secondary world is just as important as plot or character — indeed they are inexorably interlinked.

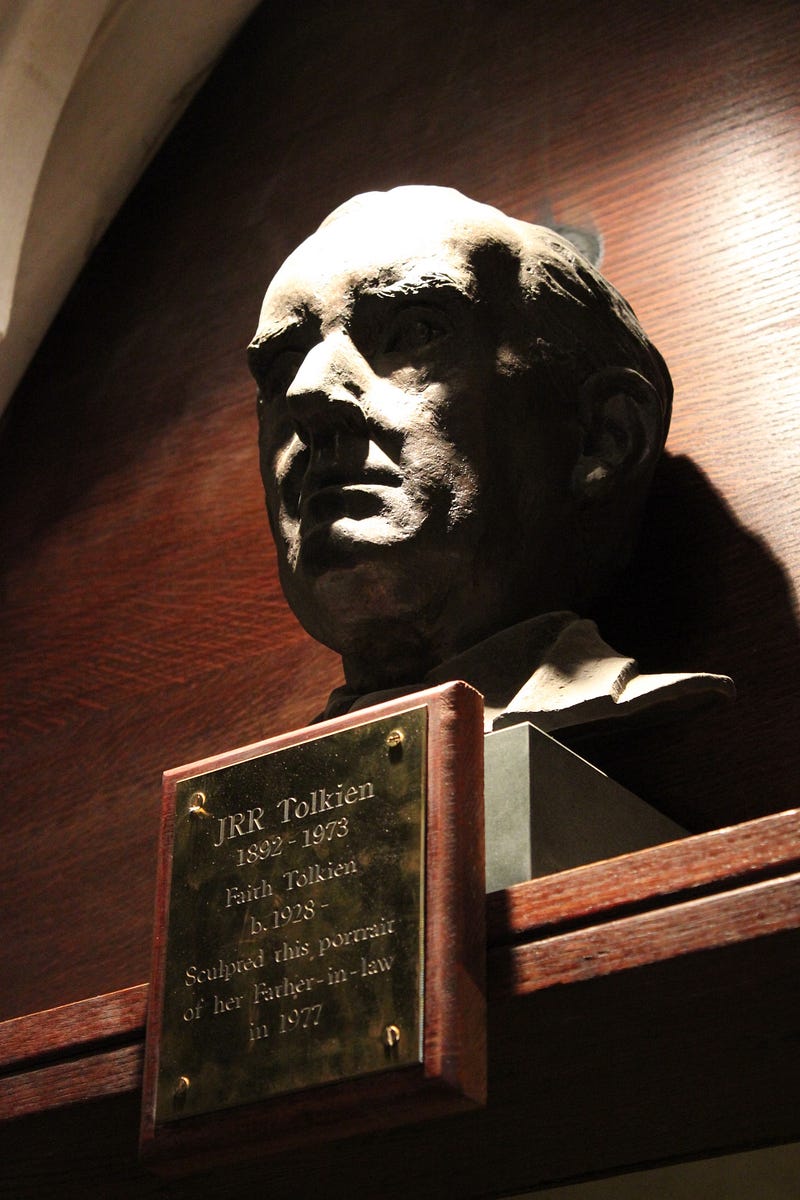

As Explored Through J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings

J.R.R. Tolkien considered the creation of his fantasy geography to be of utmost importance, not merely an accompaniment to the creation of deep fictional linguistic traditions, social histories, and mythology but tied to those elements so that each informs the other. For Tolkien, the creation of a detailed geography informed the very societies of his story; the interplay of society and geography created the depth of his world. While concentrating on Tolkien’s work, this essay argues that the geography of any secondary world is just as important as plot or character and that these other elements will be positively affected by the creation of detailed geographic elements in a work of fantasy.

Paper as presented at the 2021 International Conference for the Fantastic in the Arts.

Geography is an active and vital aspect of a constructed world, those fictional realms termed by J.R.R. Tolkien “secondary worlds.” Indeed, the greater the complexity of a secondary world’s geographic elements, the more “believable” the secondary world becomes. Complexity beneath the story’s surface, even if never fully comprehended by the reader, will alter all aspects of the story. As Gary Snyder points out in The Practice of the Wild, a culture in the real world is directly tied to its landscape (the geography which it inhabits) (Snyder 7). This is no different within a constructed world. The topographical elements of the secondary world (the mountains, lakes, rivers, forests, and seas) will inform the cultures that inhabit that world, and will, therefore, inform the characters through which the narrative unfolds.

In this essay, I concentrate on the work of J.R.R. Tolkien for, as fantasy scholar Stefan Ekman writes in Here Be Dragons, “its central position in the genre makes it a useful point of reference” (Ekman 3). Brian Attebery contends as well that The Lord of the Rings is one of the prototypes of all modern fantasy (Attebery 14–16). Tolkien’s work is, therefore, a vital point from which to begin any genre-wide discussion of fantasy, particularly fantasy which deals with the constructed secondary world.

The geography of a constructed world draws upon the skills found within multiple disciplines, from history and anthropology to science and linguistics. Mythology, folk-tale, and the whole canon of similar fantasy work also play an important role. In On-Fairy Stories Tolkien points to this process with the term “Cauldron of Story” (52), which is his method of describing how multiple source elements become blended to create something recognizable to the reader and yet also new. It is important to understand that simply drawing a line of mountains on a map, or placing a specific culture within this or that setting (a forest, a desert, a city) is not enough to imbue the world with depth. To fully access the geography of a secondary world, that geography must be completely laid out and composed with significant detail. It must be more than a generic “mountain range”; it must contain a historical and mythological dimension as well as the geological dimension. What does that mountain range mean to the people who have always lived in its shadow? How has it informed their growth and development? Once the writer begins to ask themselves questions in this regard, then the depth of the world can open and the plot can begin to take direction from the setting, rather than the other way around.

And yet, for all that Tolkien provides hints within his collected letters and essays of how this process should take place, his actual scholarly work on the method of constructing a secondary world is vague. To understand how Tolkien created the secondary world of Middle-Earth, his fiction and supporting Apocrypha must be consulted directly. It is only through a careful study of the geography of his fiction (in both its natural and administrative dimensions) that it may be possible to form an understanding of his process.

Opening with a brief introduction to some of the key concepts and terms within fantasy scholarship and a summary of some general concepts of geography, I then begin this exploration through a detailed analysis of maps and their inherent meanings, showcasing how certain map elements imply characteristics of a world by contrasting similarly-designed maps from Tolkien’s Middle-Earth and a real-world location. This cartographic discussion provides an opening for further exploration of how time is handled in secondary worlds and how time and landscape are intimately connected. Finally, I turn to the anthropological perspective and investigate how cultures and individuals are altered by their native environments (and how they, in turn, affect that environment), to show how detailed secondary world geography influences every aspect of a story.

Fantasy terminology

Of specific importance to the discussion of Tolkien’s work are four terms. The first two are categories of fantasy literature: “portal-quest” and “immersive.” The other two are the terms “secondary world,” used to describe a created fantasy world, and “secondary belief:” the level of enchantment experienced by a reader of a secondary world (also roughly defined as the ease with which a reader suspends disbelief in apparently fantastic elements).

Coined by J.R.R. Tolkien, a “secondary world” refers to any constructed fictional world which exists as a “sub-creation” of the real world. For Tolkien, “sub-creation,” as well as “secondary world,” held connections to his religious beliefs; Tolkien believed that the work of an author was, in essence, a lesser repetition of the Divine Creation (hence the term sub-creation) (“On Fairy-Stories” 49). However, while this implicit religious meaning was important for Tolkien, it is not a necessary component for the creation of a secondary world. For general use as a term within criticism, “secondary world” remains both viable and extremely useful. This is because it distinguishes a constructed world which attempts to mimic the depths and complexity of the real world from one which does not. A secondary world also carries with it an implicit notion of “secondary belief.” This Tolkien likened as similar to, but far deeper and less conscious than, suspension of disbelief. For Tolkien, a state of secondary belief implied a state of enchantment where the governing consciousness was placed automatically on hold, in the same way it might be for a child listening to a fairy-story. Because of the depth and detail implicit in a true secondary world (by Tolkien’s definition), secondary belief becomes easier as well.

Modern fantasy criticism generally accepts the idea of “fuzzy sets,” a concept explored by Brian Attebery in his book Strategies of Fantasy (12). This is a general means of grouping similar types of stories alongside each other, to better categorize and understand them and their interrelationships and development. These sets or categories are considered “fuzzy” because they are not intended to be definitive, but merely to serve as general encompassing principles. One type of story can bleed into another or be wholly contained within another, hence their “fuzzy” nature; their borders can blur. Farah Mendlesohn narrows the discussion of categorization further in her book Rhetorics of Fantasy, with her proposal of four general categories of fantasy. These categories are as follows: the portal-quest fantasy, the immersive fantasy, the intrusion fantasy, and the liminal fantasy (all of which maintain the “fuzzy” characteristic of Attebery’s sets). This essay concentrates solely on the first two of these categories, portal-quest and immersive, as these are of principal concern when discussing Tolkien.

The portal-quest is related to the emergence from a known world into an unknown world, as experienced from the perspective of the main character(s). Specifically, this does not require an actual portal within the narrative (as in C.S. Lewis’s The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe). Mendlesohn argues, for instance, that The Lord of the Rings is a portal-quest, due to the primary perspective being that of the Hobbit characters who are unfamiliar with much of the world they explore beyond their Shire (Mendlesohn 2). While the application of Mendlesohn’s portal-fantasy category to Lord of the Rings can be debated (for there are strong elements of immersive fantasy within that story), The Hobbit could more easily be considered a portal-quest in whole since, even more so than in The Lord of the Rings, the principal characters are unfamiliar with the world they travel through.

The other of Mendlesohn’s categories of interest is one I already mentioned: “immersive fantasy.” Immersive fantasy is where the world inhabited by the characters is known and normal for the characters involved, leaving the reader to puzzle out the specifics of the world for themselves from contextual clues and tangential elements. The reader does not get to experience the “new” world of the fantasy story through the eyes of an “outsider.”

Geography

Geography, from γῆ (gê, “earth”) + γράφω (gráphō, “write”), literally translates as “earth writing” (Oxford English Dictionary. “geography, n.”). In this word is found a reference to maps created through both drawings and language. But “geography” does not simply refer to the topographical elements of a landscape, it also deals in the “administrative geography” of a place, such as the geography of a political landscape.

The physical geography of a person’s (or a society’s) home surroundings influences them from birth to death, and their subsequent relationship with that geography further creates a continuing cycle of interrelated action and reaction. Thus, the individual or group acts upon the natural geography but must also conform their administrative geography to the natural (or else remake the natural to suit the administrative). In fantasy fiction, “geography” must be understood to encompass this same complexity; the natural environment (landscape) of a secondary world in fantasy may be just as complex as that within the real world, and will, therefore, have an impact on the “administrative” geography correlative to that complexity. (From now on, the use of the singular term “geography” shall assume the inclusion of both the natural and the administrative, unless a distinction is required). In his book Here Be Dragons, Stefan Ekman explores how geography is experienced within a secondary world:

Just like in the actual world, all reasonably complex secondary worlds are divided into areas of various kinds. Divisions may be geographical or administrative in nature, with areas demarcated by, for instance, rivers, mountain ranges, beaches, hedges, ditches, dykes, or simply lines on a map. Crossing from one area into another may be fraught with peril, exciting, or barely if at all noticeable. In fantasy settings, whether primary or secondary worlds, other kinds of divisions and types of areas occur as well. Two areas, while side-by-side geographically, can have quite different rules for how — for instance — time, space, and causality work. (Ekman 68)

It is this final point regarding the mechanics of “time, space, and causality” where Ekman notes one of the principal features which differentiates secondary worlds from the real world: in the real world, save perhaps within certain extreme phenomena (as with gravitational singularities), the laws of nature remain constant. Within a secondary world, the geography may be impacted by the fantastic in ways that allow for constructs that are not “natural” (such as mountain ranges the creation of which does not correspond to tectonic action, or forests where time moves differently within than without). This is imperative for an understanding of how landscape functions within fantasy because such an action of the fantastic is more than arbitrary fancy; these elements are likely to have an increased impact on both the cultures and characters of the secondary world, just as the presence of a volcano might to a culture in the real world. Such differences in geography caused by the fantastic are not to be discarded as “set dressing” and less important than plot, for such an assumption would undermine the entire premise of the secondary world. As Tolkien notes in “On Fairy-Stories”:

“Fantasy thus, too often, remains undeveloped; it is and has been used frivolously, or only half-seriously, or merely for decoration: it remains merely “fanciful.” Anyone inheriting the fantastic device of human language can say the green sun. Many can then imagine or picture it. But that is not enough… (“On Fairy-Stories” 70)

What Tolkien does not say here is how the process of deepening the fantasy-reality can be achieved. He does, however, present a model of sorts within the fantasy geography of his own constructed world: geography which contains both descriptions of a natural environment and of human (or at least sentient) action upon that world.

Mapping the fantasy world

A map, in allowing for a graphical representation of a large area of a section of fantasy geography, gives the reader an introduction to the secondary world without the need for excessive narrative description. It also serves the writer by providing certain elements of the secondary world for observation before the construction of the plot has necessarily even begun. As J.R.R. Tolkien notes in a 1955 letter, “I wisely started with a map, and made the story fit (generally with meticulous care for distances) (The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien 195). A map does more than represent the physical and administrative landscapes of a secondary world. The true power of maps is how they create depth of time and how they imply aspects of the much larger world through association.

Were a map to have “The Ancient Tower of [Insert Name Here]” marked somewhere in the northern edge of the continent, this would indicate something to the reader about the world (for one thing, that this is a world where ancient things exist). Ekman references this when discussing the map of The Shire in The Lord of the Rings (61).

Ekman rightly shows how Tolkien draws attention to the name of the Old Forest which, despite not being the only forest in the area, maintains that special honorific “Old.” As he explains, this tells us that even when there are plenty of woodlands and forests nearby, none of them is “Old” in the same sense of the Old Forest; the “Old” also implies a relationship to the Shire itself, and Hobbit settlement there. Its physical depiction on the map says more: despite that other woodlands exist (Bindbole Wood in the North Farthing and Woody End between the East and South Farthings), these appear “tamed” by the roads and settlements which surround them. By contrast, the Old Forest is a border; the Old Forest appears to lean against the Eastern edge of the Shire, pressing at it, and held at bay by the narrow line marked “The Hedge.” As is learned a little later in the story, the Hobbits do indeed have a relationship with the Old Forest, and an antagonistic one at that, many centuries old.

Contrast the above map of Tolkien’s to one of a real-world location, drawn in a similar style. Drawn by Alden Olmstead, the following is a map of Sonoma County in California. This map functions in much the same way as Tolkien’s map of the Shire does. “Petrified Forest” provides a sense of time; “Fort Ross” suggests a military of some sort; the map as a whole suggests a sense of industrial and political coherence (there are numerous communities depicted, most apparently devoted to farming and farmland, all well-connected by roads and a major highway).

Just as Ekman notes of Tolkien’s map, in Olmstead’s Sonoma County map, several elements provide access to inferred information beyond what is specifically stated: the size of a location’s name denotes either importance or population density (you know that “Santa Rosa’’ is important due to its size and the boldness of its lettering). We can infer through the inclusion of an extremely emphasized central roadway that a large degree of travel takes place regularly (such a road also hints at the organization of the society as a whole). These same elements can be found in the map of The Shire in The Fellowship of the Ring (18), with the emphasis of place names like Hobbiton and Buckland, as well as through the inclusion of many roads and an orderly representation of the Farthings.

A final and important note is the similarity between these two maps when it comes to their edges. For both, the edges of the map continue, with various hints about what exists beyond their periphery. Clearly, Sonoma County exists within the real world and is therefore surrounded by other “known elements”; there are other counties and the highway extends well beyond the borders of the map, implying high traffic beyond the local region. But the map of The Shire includes such elements as well, and the inclusion of these suggested knowns is incredibly important, for they denote that the land of the fantasy world is known (to its inhabitants). It may not be known to the reader, but the inhabitants of the secondary world are fully aware of what exists there. Ekman makes the point that such infrastructural detail alters the meaning of included “blank” spaces on such a map as well, for those blank spaces then become a hint that whatever exists in such a space is also known (as it is surrounded by knowns) and is therefore so mundane that the map author chose not to include it at all. What would instead be inferred from a map with few “knowns,” where a single road connects distant towns, and where only the word “forest” fills in great white spaces on either side? In such an instance, the blank spaces might be more readily inferred to represent actual unknowns (since they are largely uninterrupted by signs of development and can, therefore, be assumed to not exist as part of an ordered landscape, at least from the perspective of the maker of the map).

Mapping an area allows for associations to be drawn from the image itself, deepening the reader’s connection to the landscape. In the real world, these depictions allow a person to understand distance, to gauge travel times, to orientate against physical landmarks, and to comprehend social conditions: all of these aspects, too, are vital for a secondary world. Understanding the importance of geography in the real world, and taking care to transfer as much of that detail into a secondary world as possible, enhances the “believability” of that secondary world. Without this attention to detail, the secondary world is at risk of appearing thin, of existing merely to serve the plot, or some other need of the author (and not, therefore, to exist as a place to be believed in). Peter Hunt makes this point in his essay Landscapes and Journeys, Metaphors and Maps: The Distinctive Feature of English Fantasy:

C. S. Lewis’s […] huge cast of mythic and legendary figures have nowhere to live; the journeys are spiritual, notional, abstract, and they happen […] in a landscape which is described only locally. […] A comparison of Tolkien and Lewis shows that the one has very coherent invented languages, and a coherent landscape, which give a richness which has spawned many lesser imitators, whereas the other has very little coherence in his created world, but a very well-constructed metaphysic (which is, of course, essentially imitative). It is fitting that the maps which illustrate the works are, comparatively, precise in Tolkien’s case, but self-consciously symbolic in Lewis’s. (Hunt 12)

The depth of fictional landscapes is aided by how those landscapes adhere to real-world similarities; the extensive descriptions of the landscapes (often found in secondary-world fantasy especially) are not simply an overabundance of descriptive language, but rather a central aspect of what provides depth and reality to the constructed world. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why maps are so prevalent within such fantasy novels, for though they may also be found within at least a quarter of all fantasy novels, they appear to a significantly greater degree within fantasy featuring constructed and secondary worlds (Ekman, 25). The map of a fantasy world is not enough on its own, of course, to create the appearance and tone of “depth”; it will do little more than exist as part of the novel’s meta-text unless the experience of the landscape as described within the map is made into an inherent part of the narrative. Maps also imply history; they manage to create, with very little effort, the suggestion of a chronological experience to both natural and administrative geography. As mentioned earlier, Tolkien began by creating his maps, by laying out the foundational geography of what was to become the landscape for his stories. This gave him bounds for his plot and created for him both natural geographic boundaries, as well as the more potent boundary of time.

Time, as experienced by human beings in the real world (and most societies and characters within fictional worlds as well), is deeply intertwined with geographical elements. The turning of the seasons implies repetitive shifts in local geography, travel is understood in terms of the landscape through which it is to be undertaken, and both history and mythology take root in the formations of the natural world: in rock and wood, in mountain, plain, and desert. For instance, in The Silmarillion, while the landscape is not lent quite the same literary richness as the volumes comprising The Lord of the Rings, the depth of the geography is instead formed by the unfolding of the temporal dimension. That is to say, as the mythology and history of Middle-Earth is told, the geography of the world is (literally, within the narrative) constructed and reshaped (often through the will of god-like beings, rather than natural processes). As the narrative of the Silmarillion moves from the purely mythic to the historical, the landscape is given a depth of detail, transmuting from a primordial space of darkness to known mountain ranges, forests, rivers. In The Lord of the Rings, this is taken much farther due to the closer narrative frame. Concentrating on the various central characters, the reader is literally walked through the landscape of Middle-Earth, and introduced more intimately to aspects of the history permeating the landscape.

What this begins to bring to light, beyond the mere usefulness of maps for the creation of a believable setting, is how deeply the various elements of a secondary world are linked to that setting. The city-dwellers or forest-dwellers; the people who reside on the plains, or next to the ocean; all the various cultures of the secondary world inhabit an incredibly detailed landscape. The landscape is infused with their history, for these fictional people will have acted upon their environment throughout the centuries, just as the environment will have acted upon them. The Hobbits tamed the Shire, but they are also informed by the topography of that land (what would the Bucklanders be like if the Old Forest did not stand upon their very stoop?) Understanding how deeply people are linked to the landscape is important for a fantasy writer because their characters will emerge from those cultures. In a very immediate way, the characters of a novel are descended from the landscape that they were raised in, just as people in the real world are molded by the landscapes they grew up in or reside within.

Geography and time within secondary worlds

When considering the subject of time, the geographical elements of a secondary world interact directly with the story and plot. Both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are travel stories based on an archetypal adventure narrative framework: encountering troubles along the way, the adventurers follow winding roads toward their grand destination. Of course, throughout both works different points in the narrative feature differing levels of environmental description, as is needed to keep the plot moving ahead. Some periods of travel are condensed through narrative compression (when time in a story is skipped or simplified for the sake of plot), while others are described in greater detail. What is important to our discussion is that all of this geography, even if it is largely skipped over, existed prior to the narrative itself. Narrative compression of travel is far easier if the geography exists as a firm element before the story itself is spun.

Narrative compression occurs frequently throughout novels out of plot necessity. A story would become dreadfully dull if it consisted of nothing more than a minute description of detail. The needs of the story will inform what parts of the geography should be described and in how much detail. In The Hobbit, this can be seen at the end of the chapter entitled “A Short Rest” where the adventuring party leaves Rivendell. The whole experience of leaving is summed up thus:

“Now they rode away amid songs of farewell and good speed, with their hearts ready for more adventure, and with a knowledge of the road they must follow over the Misty Mountains to the land beyond” (63).

But, if the geography already exists, the writer has this freedom to jump ahead and condensed without potentially disrupting the realism of the world. This, indeed, is one of the essential factors of secondary belief, for if the writer cannot force the landscape to conform to the needs of a plot, they must instead force their plot to conform to the geography (much as life in the real world is frequently directed by the types of geography we encounter). This is why Tolkien’s emphasis on beginning the process of writing by first creating the maps is important. By laying out the geography of Middle-Earth early on, Tolkien forced his work to maintain a sense of consistency. He could still “fast-forward” through his geography by utilizing narrative compression, but in so doing, he continued to know exactly how long certain travel would take and what might be encountered (geographically speaking) along the way. Note that in The Hobbit, while the departure from Rivendell barely warrants a paragraph, the entrance to the Misty Mountains requires a much more detailed set-up:

“Long days after they had climbed out of the valley and left the Last Homely House miles behind, they were still going up and up and up. It was a hard path and a dangerous path, a crooked way and a lonely and a long. Now they could look back over the lands they had left, laid out behind them far below. Far, far away in the West, where things were blue and faint, Bilbo knew there lay his own country of safe and comfortable things, and his little hobbit-hole. He shivered. (64)

Within this, there is mention of the amount of time it took to reach the foothills of the mountain range, and on the very next page, the time taken in transit is further clarified so that the reader understands that, in the span of just a few paragraphs, “long days” have passed. But time-as-linked-to-geography then becomes a much stronger part of the narrative when Bilbo and the dwarves all begin to think about the chill air of the mountains, an unfriendly opposition to the bright summer of Rivendell:

“The summer is getting on down below,” thought Bilbo, “and haymaking is going on and picnics. They will be harvesting and blackberrying, before we even begin to go down the other side at this rate.” And the others were thinking equally gloomy thoughts, although when they had said good-bye to Elrond in the high hope of a midsummer morning, they had spoken gaily of the passage of the mountains, and of riding swift across the lands beyond. They had thought of coming to the secret door in the Lonely Mountain, perhaps that very next last moon of Autumn — “and perhaps it will be Durin’s Day” they had said.” (65)

Here, Tolkien cleverly introduces seasonal matters. Both the world and the party’s movement across the landscape are given depth while maintaining the interior perspective of the characters. The reader learns something about the overconfidence of the adventurers while experiencing a sense of the scale of the world (and while receiving a hint of foreshadowing that the journey is likely to take longer than the characters hoped). This is one of the reasons why the time-dimension in a secondary world can only be fully accessed alongside and in concert with the geography of that landscape. Ekman makes this point in regards to the development of a secondary world’s history:

“History is inextricably part of the secondary landscape, and not simply because any landscape holds inscribed on it the history of the people who have lived there. [P]ast errors are given spatial locations, past and present are juxtaposed, and the journey across the land turns into time travel” (Here Be Dragons 126).

Tolkien also made mention of this in a 1955 letter, regarding the “curious effect that story has, when based on very elaborate and detailed workings of geography, chronology, and language, that so many should clamour for sheer ‘information’, or ‘lore’” (The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien 244). The “sheer” information of which Tolkien writes here is the same as the history mentioned by Ekman; that massive amount of accumulated background information is of interest to the readers, indeed it excites them (perhaps as much, or even more, than it excites the author). Secondary belief is something that thrives not merely upon a story which is told well, but upon a story which feels real. Reality has a sense of stability to it, and if this stability is unseated without good reason it can leave the world feeling uncoordinated and artificial, the exact opposite of what is beneficial for the creation of secondary belief. In a letter regarding a film treatment of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien writes:

“Rivendell was not ‘a shimmering forest’. This is an unhappy anticination of Lórien (which it in no way resembled). It could not be seen from Weathertop: it was 200 miles away and hidden in a ravine. I can see no pictorial or story-making gain in needlessly contracting the geography.” (The Letters of J.R.R Tolkien 291)

The realism of Tolkien’s landscape was important to him, not simply because it was his creation, but because it fundamentally mattered to the story. This is a real landscape as far as Tolkien was concerned, for the story only became a story through its interaction with that landscape (to alter the geography would fundamentally alter the narrative). In Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings, some transition of the written medium to the more compact visual is handled through implied movement from location to location, by inferring the temporal dimension through methods such as establishing shots or limited dialogue references. It is a thankful grace that Rivendell in Peter Jackson’s Fellowship did not resemble Lothlórien and could not be seen “shimmering” in the distance while Aragorn and the Hobbits confronted the Ringwraiths on Weathertop’s summit. Such a treatment would have transformed the world. It would have sundered the attachment to geography for both Lothlórien and Rivendell (and the depth of their respective histories), and it would have trivialized the journey taken by the Hobbits from the outskirts of Bree to the protection of the Last Homely House.

Anthropological: society and characters

The geography of a secondary world informs the people who “live” within that world, including the characters who will be central to the story. From local landscapes to relative distance from specific types of geographical markers (mountains, or forests, or cities), geography matters. Just as within the real world, cultures are defined in part by the landscapes which they reside within or travel through. The domesticated landscape of the Shire, the sterile and decaying cities of the realm of Gondor, and the contrast between the ancestral tomb-mounds found in the plains of Rohan and the ancient fortress of Helm’s Deep (named after a mythic hero), are all examples of how the landscape influences cultures and is influenced by them in turn.

I have chosen to concentrate this essay on two specific races from Middle-Earth to establish this process of mutual development between a constructed landscape and the people who inhabit it. Tolkien’s elves present a dynamic and complex study due to their nature as semi-immortal beings, and also because that long lifespan lends itself to cultural variation (and especially variations due to geographical specifics). Being able to explore the differences in a culture which share a root ancestry (oftentimes one which is barely a handful of generations removed from the very first elven people of Middle-Earth) presents us with the chance to witness how a species with such a potential for static societies can alter and diverge from their origins. While war and other hardships are frequently one factor in this continual growth and change, the immediate environment is another. The second race I concentrate on are Hobbits, the main focus for so much of Tolkien’s direct narrative. Being a people who were once nomadic but who are encountered as long-settled colonizers, ones living an extremely peaceable and even relatively modern existence (at least, a comfortable one), they present a perfect contrast to the more mythical and fantastic elves.

Elves: Time, as we have already seen, is linked to geographical elements. But, whereas in the real world there are finite limits to the behavior of time (within the realm of common experience), within a secondary world the nature of the temporal realm can be wholly different due to the injection of alternate temporal and physical laws (or their absence). And yet how time acts still informs the environment and the people who reside within it, just as it would under real-world-similar conditions. This is most clearly seen in the elven folk of Middle-Earth. These are beings who, if not exactly divorced from the flow of time, are not affected in the same way even as the natural landscape. Save sickness or violence, they never die, nor show any outward sign of wear. And yet this aspect of their existence leaves them burdened by a great weight, for all other physical things (even the mightiest of elven works) is ground down by time. Though the natural elven life spans millennia (barring violence), their creations will all fail and their greatest deeds dwindle or become undone. Legolas explains this to his companions in The Fellowship of the Ring:

“Nay, time does not tarry ever,” [Legolas] said; “but change and growth is not in all things and places alike. For the Elves the world moves, and it moves both very swift and very slow. Swift, because they themselves change little, and all else fleets by: it is a grief to them. Slow because they do not count the running years, not for themselves. The passing seasons are but ripples ever repeated in the long long stream. Yet beneath the Sun all things must wear to an end at last.’ (Lord of the Rings 436–7)

Within Tolkien’s primary works (The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings), there are three elven societies encountered through the narrative which are contemporaries to the main plot. Rivendell is perhaps the best-known, as it is visited in both works. The realm of Mirkwood, a dense and dark forest landscape, is explored in The Hobbit and mentioned in The Lord of the Rings (Legolas is a prince of Mirkwood’s elven kingdom). Finally, the mysterious land of Lothlórien is only mentioned or encountered within The Lord of the Rings. The most important takeaway is that each represents its own separate biome of sorts, with each elven society having progressed in different social directions. Since elves do not “evolve” as such, but remain biologically static (unless acted upon by some outside force), the millennia of divergence between these groups takes the form of social differences, cultural shifts, and shifted language norms (somewhat appropriate for a fictive species created by a philologist).

In Rivendell, the landscape is mythic and yet relatable. Indeed, it is called “The Last Homely House” (The Hobbit 56), a reference to its position as the last bastion of civilization between the regions of the Shire and the distant lands beyond the Misty Mountains, while also implying warmth, comfort, and safety. Geographically, the elves built Rivendell in a defensible location, a deep and hidden gorge, at once near enough to friendly regions and yet removed from direct threats (at least at the time of its founding, during early conflicts with the evil Sauron). Just as we shall see with Lothlórien, Rivendell is also a site of magical interference with the natural laws of the world (interference carried out through the will imposed on it by the elven lord Elrond via his Ring of Power). Though the changes wrought on the landscape of Rivendell are not as immense as those in Lothlórien, it remains in a state that the Encyclopedia of Fantasy describes as a “polder” which, in this context, means “a toughened state of reality.” Within Rivendell, time passes differently than in the outside world, and the experience of weary visitors is one of being rejuvenated. Rivendell’s boundaries are more than a cliff and secret path; it is contained within a different state of reality (if only slightly) than its surroundings. Curiously, though the magic of Elrond and his ring act upon the region, Rivendell maintains its seasonal differentiation (though the effect of harsh seasons is mitigated down to almost nothing). In many ways, not the least of which in terms of its usefulness to the plot, Rivendell provides a nexus point: a gateway between lands, and therefore a form of crossroads. The elves who live there have relatively frequent contact with outsiders and travel widely within the world.

Mirkwood is similar to Rivendell in that it maintains contact with the world; the elven society established within Mirkwood in many ways relates even more closely to the norms of humans than to the elves of Rivendell. There, the elves maintain a kingdom where trade with the outside world is frequent and though the elves themselves are still “fey” creatures possessed of innate magic, they are also quite relatable as flawed people, including in their proclivity for getting drunk at festivals (The Hobbit 172–3). Their relationship to their landscape is, as is often the case with elves, a symbiotic one. Nature and elven society coexist, with the elves doing little to shepherd the landscape, save by defending certain areas from the encroachment of monstrous creatures (such as the spiders of Mirkwood, which are arguably not natural inhabitants of that environment themselves).

It is, however, within Lothlórien that the largest effect on the geography of an elven settlement takes place, and compared to both Rivendell and Mirkwood it provides a powerful example of how such a relationship defines a culture within a secondary world. Like Rivendell, Lothlórien is maintained magically through the power of the Lady Galadriel as set forth through her command of another Ring of Power, and here (to a far greater extent than in Rivendell) time is a malleable element which differs sharply from time outside the forest’s borders. Formed of mallorn trees (a species originally heralding from the soil of Valinor, the mythic “undying” land from which elvenkind originally came), Lothlórien represents a wholly unique and cultivated landscape. These are not the natural contours of the gorge in which Rivendell lies, nor the sort of forest which springs from ordinary processes. Lothlórien not only exists as a protected reserve from the flow of natural time, but it also acts as a preserve for a type of flora not found anywhere else on Middle-Earth, the mallorn (pl. mellyrn) tree. By introducing mellyrn to the local environment, the elves have cultivated a symbiotic relationship with that species; it is from the mallorn that the elves acquire the entire scope of their building material (not merely for their homes, but for their clothing, weapons, and river-based transportation as well). The elves of Lothlórien have “terraformed” (or, more aptly, vallinor-formed) their environment to suit their needs, and in so doing their culture has been directed down a very specific socio-evolutionary branch. They have become significantly more reclusive than their kin in Rivendell or Mirkwood, and it eventually becomes rare for them to speak or understand languages other than their own, and uncommon for them to travel beyond the borders of their domain.

Hobbits: Hobbits are a prime and important example of how the geography of a secondary world and the cultures inhabiting it influence one another. When observing the map of the Shire included in The Lord of the Rings, it becomes quickly apparent that it “denote[s] Hobbit control of the landscape” (Ekman 53). The Farthing borders on the map (and indeed the very existence of the Farthings themselves) suggest a sturdy centralized social order, a point backed up by elements of an advanced social structure found within the narrative itself, such as the existence of a capable postal service (The Fellowship of the Ring 27). The time-dimension of their relationship to the landscape is also explored within the preface to The Fellowship of the Ring. In their earliest days, the Hobbits built in their traditional style, burrowing holes into the ground and expanding them out into a series of tunnels and rooms. However, as time wore on and population density increased, new developments took shape out of necessity, and these were in the tradition of Men (above-ground buildings built of timber and stone). By the time of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, the whole of the Shire is quite built-up and even includes overt hints of industrialization (in the form of the quarry listed on the map of the Shire included in The Fellowship of the Ring).

Hobbit society shares many aspects in common with modern society. Mills, inns, quarries, even the structure of their daily lives around various mealtimes, all hint at a sort of stable social order which is more familiar to modern life than to the otherwise semi-medieval setting apparent throughout the larger story.

This creation of a recognizable and sympathetic culture is important, for it allows the reader to become familiarized with Middle-Earth through the eyes of a people who are already themselves comfortable, at least within their own realm. The Hobbit society’s lack of (and uninterest in) knowledge about the broader world (save for what exists in their myths and legends) is of further service to the plot later on, as it allows more of the vast histories and geography to be illuminated by their travel and the questions they pose.

Conclusion

J.R.R. Tolkien provided the world with a new type of fantasy fiction through his nearly five steady decades of work on his secondary world, thus cementing his creation as one of the central pillars of the fantasy genre. The way he did this, through the creation of secondary worlds fostering what he called secondary belief, provided future generations of writers with an unprecedented template from which to draw inspiration. However, that template needs to be accessed directly through Tolkien’s fiction since his overt scholarship on the subject is minimal (contained primarily within a handful of short essays and personal letters). Therefore, it is to his creation itself that new generations of worldbuilders must turn in order to glean the specific methods through which Tolkien devised his secondary world. Geography, and its direct influence on culture and character, is a topic that has been explored to a lesser degree than other areas of Tolkienian study, and yet concentrating on the geography allows us to begin forming a “template” of sorts from which to replicate and expand upon some of the techniques which Tolkien employed in his own world construction. While remaining just one cornerstone for such worldbuilding, geographic concerns connect to so many other areas of fantasy that they must be considered one of the fundamental aspects of secondary-world construction.

I intend for this essay to serve as a medium through which a deeper understanding of these processes take place so that they can be utilized by writers, especially writers who might be searching for a primer on worldbuilding. By taking a journey from the foundations of fantasy scholarship and geographic concepts, through the different ways geography informs time-dimension and travel, as well as the development of unique cultural traits, I hoped to provide a detailed sense of why geography matters so much within a secondary world. Alongside that journey, my discussion of maps aims to provide readers with at least one specific tool through which they can access the larger principles in discussion within this essay and thereby apply them directly to the creation of their own secondary worlds.

Secondary-worldbuilding is a process which extends beyond “fantasy” genre literature, and naturally expands into any type of secondary world where the “enchantment” of the reader is a primary goal of the author. Understanding these methods laid down by Tolkien does not do a writer’s job for them, but it does lay some pavement along the road to depth and adventure.

Works Cited

Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Indiana UP, 1992.

Ekman, Stefan. Here Be Dragons: Exploring Fantasy Maps and Settings. Wesleyan University Press, 2013.

Hunt, Peter. “Landscapes and Journeys, Metaphors and Maps: The Distinctive Feature of English Fantasy.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 1, 1987, pp. 11–14., doi:10.1353/chq.0.0498.

Mendlesohn, Farah. Rhetorics of Fantasy. Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

Olmsted, Alden. “Hand Drawn Map of Sonoma County.” Tumblr, 4 July 2016, aldenolmsteddrawslocal.tumblr.com/image/146906966165.

Snyder, Gary. The Practice of the Wild. Counterpoint, 2010.

Tolkien, J. R. R. “On Fairy-Stories.” The Tolkien Reader. Ballantine Books, 2001, pp. 33–99.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Fellowship of the Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings. Del Rey/Ballantine Books, 1994.

Tolkien, J. R. R., and Christopher Tolkien. Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: a Selection. Edited by Humphrey Carpenter, Allen & Unwin, 1981.

Tolkien, J. R.R. The Hobbit. 36th ed., Ballantine Books, 1977.

Works Consulted

Burtscher, Irmgard. Tales from the Kalevala. Translated by Hartmut Schiffer, Rudolph Steiner College Press, 2007.

Crawford, Jackson, translator. The saga of the Volsungs — with The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok. Hackett Publishing, 2017.

Day, David. The Illustrated World of Tolkien. Thunder Bay Press, 2019.

Ellis, Peter Berresford. The Mammoth Book of Celtic Myths and Legends. Running Press Book Publishers, 2008.

Hirsch, Eric. “Landscape, Myth and Time.” Journal of Material Culture, vol. 11, no. 1–2, 2006, pp. 151–165., doi:10.1177/1359183506063018.

Hollander, Lee M. The Poetic Edda. University of Texas Press, 2015.

Le Guin, Ursula K. Steering the Craft: a Twenty-First Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story. Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015.

Lonnrot, Elias. The Kalevala: the Epic Poem of Finland. Translated by John Martin Crawford, Pacific Publishing Studio, 2011.

Rothfuss, Patrick. Name of the Wind: The Kingkiller Chronicle: Day One. DAW Books, 2007.

Stilgoe, John R. Old Fields: Photography, Glamour, and Fantasy Landscape. University of Virginia Press, 2014.

Swinfen, Ann. In Defence of Fantasy: a Study of the Genre in English and American Literature since 1945. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984.

Terry, Patricia. Poems of the Elder Edda. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.