We’re Going on a Stag Hunt

A storytelling approach to economics Cooperation is the best possible solution, so why are humans so frequently bad at it?

YOU hold the bow up to the light, appraising the fine curve; its taught spine made tense by the strung line of cured gut affixed to both ends. This is a good bow, you think, and the thought brings a smile to your heart. Today, with this bow, I’ll feed my whole family.

You’re a hunter, part of a community of some hundred or so souls, all living on the edge of the woods. Electricity and modern conveniences are still several hundred years away, but you’re happy with what you have. Sure, times can be tough, but they could also be much worse. And, with the prospect of the upcoming hunt, and all the meat it will provide, you’re feeling optimistic about the future.

After all, today you and the other hunters from your community are going out to hunt a stag.

The Great Stag has been sighted several times in the last few weeks. With winter approaching, you know you need to stockpile as much cured meat as possible to make sure your family survives. Sure, there are plenty of game rabbits in the forest, but these animals don’t satisfy the belly in the same way that a massive animal like the Great Stag will. You’re feeling certain that, with the help of your companions, you can bring in enough meat from this single hunt to stave off even the worst of winter’s chill.

Soon, you gather on the edge of the forest with your fellows to prepare your plan of attack.

Hans, who often talks the loudest, starts the meeting off.

“So,” he says, holding up his own bow, “I knocked an arrow back earlier, and this thing barely lobbed in fifteen feet! How, exactly, are we supposed to take down the Great Stage with something so puny?”

You look down at the bow which, just shortly before, you’d been admiring. Suddenly, it seems quite small for the task ahead.

But then Bernard steps forward. He’s older that most hunters — he’s popular in the community, but some minor heart trouble has led some to suggest he might not be the best hunter around. He holds out his own bow so that everyone can see it.

“Hans is right, sure,” he says. “This bow can’t shoot far on its own. But! And here’s the thing…” he knocks an arrow to the string, “we don’t need it to! If we all work together to take down the Great Stag, none of our bows need to do anything more than they were designed to.”

“But how?” you ask, stepping forward.

“Let me tell you, let me tell you,” Bernard smiles in your direction. “The Great Stag is very fast and very smart. If we try to come at him one at a time, we’ll fail. As a matter of fact, he is so crafty, that it will take every single one of us, each of our bows, to make this work. We need to wait, carefully in the woods. When the time is right, we will surround the Great Stag on all sides, hem him in, and then we will all fire a single arrow. If we work together in this way, we’re certain to take him down.”

At first, the crowd seems pleased, and you nod, impressed with the plan. But Hans, upset at being ignored, suddenly breaks in.

“Yeah,” he says loudly, “alright. But what happens if someone chickens out?”

Bernard nods, sagely. “True enough,” he says, “everyone is needed. We have to support one another! If even one person backs out, we won’t be able to hem in the Great Stag. Then, knowing that the forest here isn’t safe, he’s certain to flee and never return. So we all need to get together and back each other up!”

The crowd again nods in agreement, but you notice that Hans looks a little mutinous. Still, as the hunt begins and you all head into the forest, you’re feeling good about the hunt. After all, even by splitting up the meat from the Great Stag between all the hunters, you’re certain to have enough meat each to put plenty away against the coming winter. That’s far better than the usual rabbit hunting which never manages to feed more than a couple of people for a single day.

However, as the day wears on and you trudge with your fellows deeper into the forest to the place where you will wait for the Great Stag, a snarl of doubt climbs up the back of your neck as you remember the look on Hans’s face. After all, if even a single person decides not to follow through with the hunt, the Great Stag is sure to escape the trap. You start keeping an eye on Hans and you notice that, as you all move through the forest, his eyes keep flicking to the occasional rabbit in the underbrush. Sweat beads his brow even as a cool autumn breeze rustles the foliage overhead.

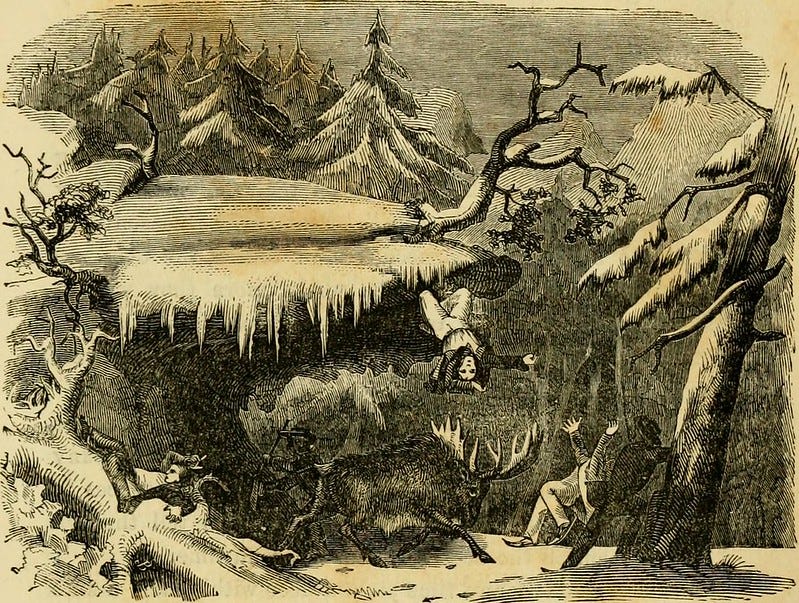

He’s going to chicken out! The thought hits you like a weighted club. Suddenly, all you can picture is your family, cold and hungry as winter sets in and all the game vanishes. You start to think about how much time it takes to catch rabbits, and how little meat’s really on them. It will take weeks of hard hunting just to keep your family barely fed, you think. And if everyone else is hunting rabbit as well…

You look around and recognize the signs of anxiety about several of the other hunters as well. You can’t be the only one realizing the danger. Quickly, you sum up the problem in your head:

It will take many days of careful tracking and waiting to corner and kill the Great Stag. Once you do, you’ll get a share of the meat alongside all the other hunters. However, if even a single hunter backs out, or if the Great Stag catches wind of your group, it will certainly flee and everyone will go hungry.

There is also no certainty of the Great Stag even showing up, you think, starting to feel even more anxious. Besides, you are certain that Hans is close to killing the wild rabbits he comes across, which will almost certainly ensure that the Great Stag (scenting the kill) will stay far away. Hans will go home with something and the rest of you will be left to return home hungry! The more you think about it, the more it seems certain that Hans will ruin the hunt for the Great Stag. Hunting the stag seems desirable, but increasingly implausible.

Better to kill the next rabbit I see, you think, than to hope that the stag appears or trust to Hans to think of anyone but himself first!

THIS is the classic problem of the Stag Hunt, a game theory concept turned into a story by the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. I’ve altered it somewhat for the sake of narrative, but the gist remains the same.

In order for the group of hunters to succeed, they must all work together. If a single hunter backs out, the plan is ruined. The problem is one of trust, of faith in the whole group. If all the hunters believe that all the other hunters will remain true to the cause, they will almost certainly work well together and catch themselves the stag. If they believe that any one of their number might succumb to the temptation of hunting the more immediately available rabbits, however, then the plan is almost certain to fail.

This is because human beings are remarkably good at noticing opportunities for short term gain yet usually quite bad at maintaining the sort of optimism required for long term gain. It seems logical, from an individual perspective, not to risk everything on a single idea (that all the hunters will work together and none will deviate). And yet, should any hunter break the pact, not only will they not get a share of the greater prize that is the stag, but will acquire a significantly worse-off short term gain in exchange.

In his remarkable book Talking to My Daughter About the Economy, Yanis Varoufakis (the former finance minister of Greece), outlines how markets fail because of this lack of trust:

Just like Rousseau's hunters, entrepreneurs struggling to remain profitable in a market society are play things of their collective expectations. When the group is optimistic, their optimism is self-fulfilling and self-perpetuating. And when it's pessimistic, their pessimism is also self-fulfilling and self-perpetuating The fact that they know this to be the case only makes it all the more certain that it is — and just like Rousseau's hunters, they may end up chasing hares even though they would rather not.

This is why the unemployment deniers are wrong: because the labor market is based not just on the Exchange value of labor but on people's optimism or pessimism about the economy as a whole and so across-the-board wage cuts may well result in no new hirings, or even layoffs. (99)

It is vital, therefore, to understand the importance of the community surrounding us and its role in our own greater good. It can seem like a good idea to run off into the underbrush after the most immediate personal gain… but doing so will only doom us, in the end, to starvation. Worse, our fear and selfishness dooms others as well, since for the whole to succeed there needs to be belief; there must be faith in our community for the community to remain strong.