Universal Income is a Right

It’s also the way we save democracy Did you know that UBI was almost signed into law in the ‘60s? This is an idea whose time as most certainly come. The question is: do we have enough democracy left to make it happen?

it’s also the way we save democracy

There are already hundreds of articles tackling the explosive entry of Universal Basic Income into the public sphere. As Rutger Bregman pointed out in his book Utopia for Realists, UBI is not an exclusively new principle — it has even been extraordinarily close to achieving a Presidential signature in the past.

In 1968, a number of the most famous an influential economists of the era penned a letter, supported by over a thousand other economists, in support of Universal Basic Income.

Richard Nixon advocated strongly for UBI during the sixties, apparently hoping to position himself in the role of presidential innovator. While his career will be remembered for other reasons, his early acceptance and support for Universal Income has been mostly buried in dust. In 1968, a number of the most famous an influential economists of the era penned a letter, supported by over a thousand other economists, in support of Universal Basic Income (.pdf page 233).

Nixon, seeing the way the wind was blowing and hoping to cement his legacy, moved ahead with full support for UBI. Of course, studies were needed. What sort of detrimental effects would UBI have upon the working populace of the United States? Would the fears of the more conservative members of the House and Senate (on both sides of the isle) be realized in any f the carefully planned trial studies? The answers came in with a resounding answer: Under UBI, paid work declined an average of nine percent — and even this number was later proved to be higher than was actually the case.

More important were the positive gains: the people who used their newfound support to go out and advance their education, to support their families, and to generate greater community and social goodwill.

And then came Martin Anderson, one of Nixon’s advisers. A massive fan of the writer Ayn Rand, Anderson looked on fearfully at what he surely believed was an oncoming apocalypse of moral degeneration. But he had an ace up his sleeve which he was certain would prevent the diabolical plot of universal basic income from ever seeing the president’s support: the Speenhamland incident.

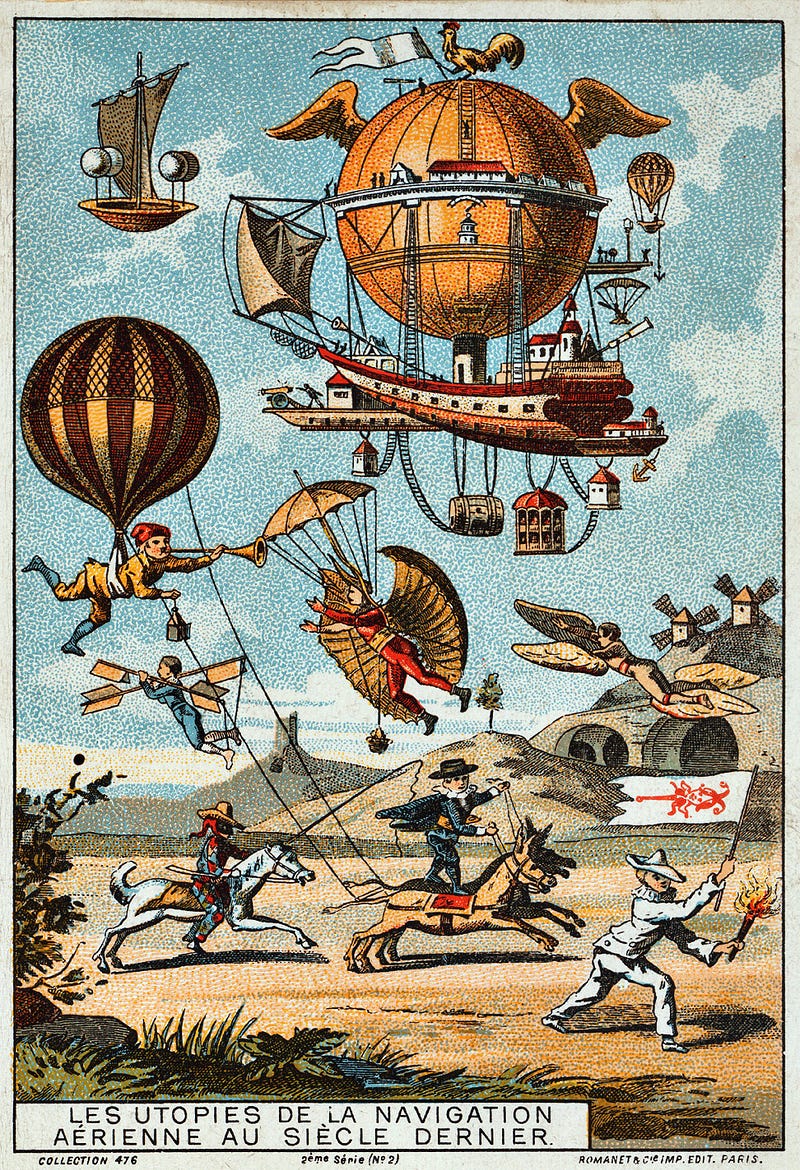

It seemed that the system might spread throughout England — and, if it had, the concept of Universal Basic Income might have arrived two-hundred years ago as a normal part of society.

In Utopia for Realists, Rutger Bregman brings up the dark mark of a much earlier exploration of basic income, one conducted in the year 1795. This study, which was ultimately proved to be corrupt in every possible way, denigrated the idea of basic income to such an extent that even a hundred and fifty years later it’s condemnations would still haunt the very idea.

The city of Speenhamland had a unique system in an era of England’s “poor law.” Under the poor law, people were separated into two categories: those “deserving” of support (elderly, children, and women) and those deemed capable of work. But in Speenhamland, everyone received the same amount of assistance. It seemed that the system might spread throughout England — and, if it had, the concept of Universal Basic Income might have arrived two-hundred ago as a normal part of society.

And then a group of conservative thinkers and religious leaders gathered together and decided to destroy the dangerous cancer of equality. Concerned that equality for the poor would lead to lax workers and the general moral degeneration of society (especially concerning to these men was the idea that women might be free to make their own way in the world), this group set out to so severely damage the name of basic income that it would never be considered again.

Their report on Speenhamland was falsified in every way, but the political climate of the time was hostile to the working people, and the idea of support for all was crushed. In its place a horrifying system emerged where the “right to work” principle ruled, creating an appalling human rights nightmare that would last for a century.

Back in the 1960s, Nixon was horrified by the report. From there on, his fight for UBI weakened consistently. Though he continued to push for diminished forms of UBI, the work of the devil had been done. By the time 1970 came to a close, conservative thinkers were scenting blood in the air, for the tide had turned. Running a slanderous public opinion campaign against all things “welfare” conservatives were able to sway the public and push for positions increasingly removed from universal income. By the time Bill Clinton entered the Oval Office in the 1990’s, it was even in vogue for the top Democrat to lambaste basic income, and welfare in general.

It seemed that the grand old idea of an equalizing social agent, of an income offered as a human right — rather than a mere privilege — was dead for good.

Enter the repercussions of the 2008 economic crash and the Great Recession which followed — and, in many ways, continues to follow. With this recession came a shaking of public belief in the infallibility of the economic models trusted by the government, and in the so-called experts calling the shots. It suddenly became clear that there was something disastrously wrong with the world of economics; that “business as usual” could no longer be allowed.

Out of this simmering cauldron came a revivification of the old idea: maybe everyone deserves the right to an “income floor” as Nixon put it. Perhaps financial stability should not be a privilege after all. Into this window of opportunity, UBI surged once more.

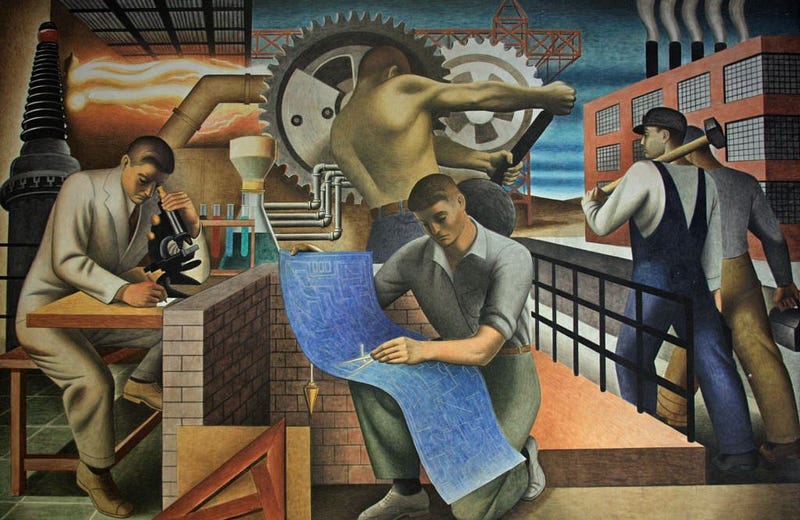

One of the defining arguments for UBI — one which has always been with it, but which carries far greater importance in the modern technological world — is that of mechanical production and its effect on the workforce.

In the 1960s, massive alterations to the way factories handled production were already underway. Automation was becoming something normalized in a larger and more profound way than ever before. Economists and business leaders were concerned and even began looking for options. One of these was basic income.

Fifty years later, the same idea would arise, though this time with even greater credence. Robotic construction processes are pushing forward at an incredible pace and they will continue to put people out of work. No amount of retraining will make up for the loss of active positions. For a time, as people lose their jobs and flood the markets with cheap labor, there will be occasional upswings — where it becomes cheaper to hire human labor than to use machines — but the overall trend is toward the utter removal of the human being from the process of production.

As this process expands, eventually, there will be no place for millions of workers — even more advanced positions are in danger of succumbing to the market goal of eliminating its human component. And, what’s more, without strong outside restrictions, the markets are utterly incapable of self-correcting for this behavior. Those markets which innovate and push for the cheapest possible means of production will survive, and those that do not will, ultimately, crumble.

This is where UBI steps in. Not merely as a placeholder for work, but as a fundamental transition away from a society obsessed with commodification.

A Universal Basic Income plan does more than merely add a few dollars to people’s wallets. In test after test across the world, results of UBI initiatives show a remarkable increase in social stability and well-being. For one thing, UBI evens out one of the greatest flaws in the market system. If people are out of work, they cannot buy things. As this cycle worsens, eventually, nobody works and nobody buys. Under UBI people can always afford to buy something — there will always be some room for the market to tick on.

But the value I see in UBI extends beyond the market — because there is, in fact, more to human existence that commodification and market systems. Markets are just one way of structuring our societies, they are by no means the only way: they are, also, by no means the point of existence.

What UBI does is introduce a fundamentally system-changing concept into the market-saturated global society. The idea that all people, regardless of circumstance, deserve all the basic elements of life. Food, security, shelter, education: these are not privileges, these are absolute and unequivocal rights. UBI cements this as reality. By providing every single person, regardless of status, income, race, or background, a set amount of money upon which they can account for all their basic needs, the very concept of what it means to be a citizen changes; the very notion of what our society considers “human” changes.

There are many arguments against UBI — most coming from people who generally can’t sum it up much better than the religious conservatives of the 1795: so-called “moral degeneration.” One thing is true: the complexities of implementing a system like this are immense. Once implemented, the system will need to be monitored carefully. It may be that, alongside UBI, other initiatives, such as State or Federal rent caps need to be implemented. As one part of the complex web of society shifts, others must alter to accommodate the new position.

Yet complexity is hardly a good reason to avoid something — especially when that something promises to be so dramatically transformative, at a very real level, for the people who comprise society. Those at the bottom are in dire need of a support mechanism — one which cannot be held over their heads to leverage whatever the ruling party at the time believes is “good behavior.” In order for our democracy to function, we need to place the ability to control ones own life back in the hands of the currently powerless and eternally disenfranchised. The social alteration would be dramatic, as would the renewed solidity of the market system on which we currently rely. In all ways, UBI is a winning move. The question is simply: can we undo the damage caused by those 1970’s conservatives? Can we ensure that the public has fair and easy access to the real facts about UBI?

I hope so.